So Long For Now, National University Team

A little over two years ago, the U.S. Ski Team introduced the National University Team (N-UNI) to integrate top American collegiate racers into the elite development pipeline. The pilot program was described as a “triangle agreement between the USSA, the athletes and their individual NCAA coaches [that allows] nominated athletes to compete for their respective university teams while having expanded year-round access to and support at training camps and additional races.” For the legions of ski racing athletes, coaches, parents, and fans who hoped to keep ski racing and education viable parallel pursuits, it represented a bright light of possibility. U.S. Ski & Snowboard recently pulled the plug on the N-UNI team, but the enlightenment remains.

The modestly-sized UNI team included six male collegiate racers, evenly split between the Eastern and Western Regions, and addressed what is cited as a major shortcoming of collegiate racing: lack of training volume. NCAA rules prohibit teams from training together in the offseason, but allow them to train under the umbrella of a national federation. By providing extensive offseason training and support at NorAm competitions throughout the winter, all coordinated and overseen by coach Peter Lange, the UNI team sought to bridge the gap between college racers and full-time national team athletes while broadening the scope of athlete development.

Did it work? “Yes!” says Kevin Francis, head alpine coach at Montana State University. “It was exactly the support we needed as college coaches – support in the summer and at NorAms.” MSU athlete Garret Driller, who went directly from high school to college and landed himself on the U.S. C Team as a rising senior, is the poster child of the program. In one more year Driller will be able to race full-time armed with the confidence of a mechanical engineering degree. “The amount of school Garret had to miss was tough,” says Francis, “and definitely college racing limits your starts (college athletes can manage 25-30 starts versus 45-50 for USST athletes) but it wasn’t bad.” Francis notes that all UNI athletes were successful: “Maybe not in the ‘making criteria’ sense but with what they were able to do with skiing and college … they were successful.”

Did it work? “Yes!” says Kevin Francis, head alpine coach at Montana State University. “It was exactly the support we needed as college coaches – support in the summer and at NorAms.” MSU athlete Garret Driller, who went directly from high school to college and landed himself on the U.S. C Team as a rising senior, is the poster child of the program. In one more year Driller will be able to race full-time armed with the confidence of a mechanical engineering degree. “The amount of school Garret had to miss was tough,” says Francis, “and definitely college racing limits your starts (college athletes can manage 25-30 starts versus 45-50 for USST athletes) but it wasn’t bad.” Francis notes that all UNI athletes were successful: “Maybe not in the ‘making criteria’ sense but with what they were able to do with skiing and college … they were successful.”

Driller was the only UNI athlete to make U.S. Ski Team criteria, which no longer designates a separate men’s development team. He, along with fellow C Team members and full-time college students Jett Seymour (University of Denver) and Erik Arvidsson (Middlebury College), will continue to utilize U.S. Ski Team training opportunities, though without the formality of the UNI team structure. Several other athletes were able to attend spring term and find additional training with other groups later in the season. According to Tiger Shaw, the collaborative aspects of the UNI team structure will endure. “[The UNI Team pilot program] showed that we all can benefit from better collaboration, embedment, and coordination between college skiers and the USST.” U.S. Ski Team Alpine Development Director Chip Knight confirms that the national team’s mentality towards skiing and college has changed: “What’s gone is the explicit funding, but the UNI Team program opened the door for college athletes in our development system. The shift that’s happened is that the coaches are willing to work to tailor the program.”

Onlookers understood that the N-UNI team was funded by Dan Leever, the engineer behind Team America; when contacted, he said he preferred to leave it to others to confirm or deny. This season Leever will continue to fund comprehensive training opportunities for independent and collegiate athletes through the Team America Foundation, under the direction of Lange.

AND WHAT ABOUT THE WOMEN?

Although Knight admits the shift in mentality has been slower with regard to women, he explains, “We’ve made inroads for both genders.” Nina O’Brien and Tricia Mangan both attended college last spring, and joined other training groups to accommodate their schedules. Dartmouth rising senior Foreste Peterson, while not officially on the U.S. Ski Team, is being integrated into some offseason training projects both on-snow and at the Center of Excellence. “We have a more flexible minded approach,” says Knight who maintains, “We’re getting there!”

BENEFITS OF COLLEGE SKIING

From Lange’s perspective, the No. 1 deficiency the UNI team addressed was helping young male athletes mature into men. “Part of the problem with skiing in the U.S. is that we don’t do that here. Too much of the year is spent being directed. We tell them where, when and how to train and we also tell them how they should feel about it. ” Managing college and athletics, however, forces them to make choices, which is empowering. As Lange describes, when kids are faced with the three components of college life – social, academic, and athletic – they can be good at two but not all three. “College forces these decisions,” says Lange, “and that is empowering. It gives young people belief in themselves.”

Beyond general maturity, college skiing also affords time for physical maturity and technical development. Being forced to ski exclusively slalom and GS – and equal doses of both – leads to a solid technical base to support multiple events in the future. Jonathan Nordbotten, who rejoined the Norwegian team after four years racing for UVM and toggling between the NCAA/NorAm circuit and the World Cup, notes that the mid-winter collegiate schedule can be exceedingly productive for training. This is especially true on the East Coast where venues are relatively close to each other. “Each week through the winter you get four days of good training between races with minimal travel,” says Nordbotten, currently the 17th-ranked slalom skier in the world.

Another less visible but oft-cited benefit is the self-assurance that comes from more actively organizing and managing your training. “Before [while on the Norwegian junior team], I was oblivious. I just got my program and did it. In college you had to be your own coach and seek your own development,” says Nordbotten. “It took a lot of tough choices.” One of those for Nordbotten came after his second year at UVM, when the Norwegian team offered him a full-time spot on its roster. “If I quit college after two years, it doesn’t give me anything,” he reasoned, and chose to stay at UVM and help both his team and his future options.

Finally, managing college and athletics makes just ski racing seem a whole lot less stressful. Driller recalls finishing his winter academic finals at 11 p.m. at Dartmouth the night before NCAA Finals. “There was no other option,” he explains. “It was that or fail.” After this year Driller will need just one extra semester, with a light load, to graduate. The prospect of ski racing without going to college is enticing. “It’s going to be a lot nicer, the mental stress level will be much less.”

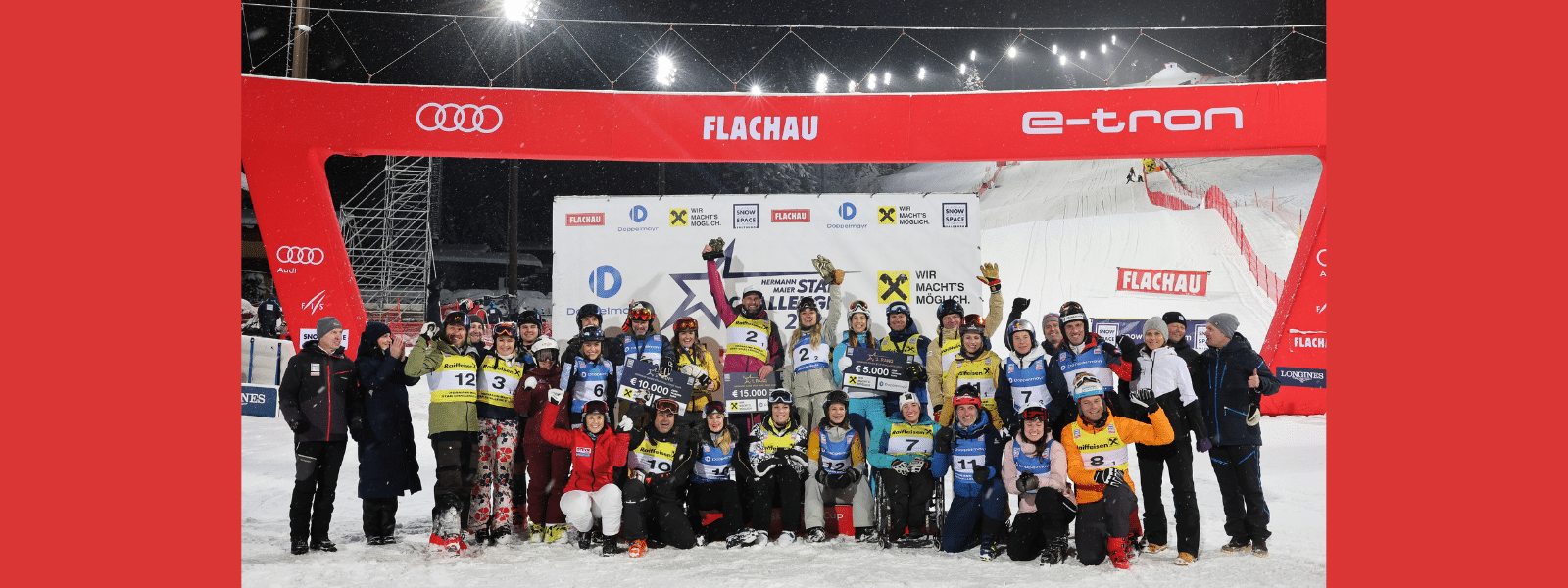

Brian McLaughlin, Griffin Brown, Alex Leever, and Garret Driller of the 2016-17 N-UNI team. Image Credit: Alex Leever (Instagram)

WHY THE UNI TEAM? WHY NOT!

The stat remains: Since 2005, we, as a country, have put five development team male athletes (Tommy Ford, Nolan Kasper, Ryan Cochran-Siegle, Bryce Bennett, and Travis Ganong) into the top 30 for a season. As Lange suggests, “Why not try something new?” Regardless of its current status, the mere existence of a UNI team may already be having some effect. In 2016, seven NCAA All-American honors went to Americans. In 2017, that number jumped to 11. Indeed, Driller’s example of going straight to college and continuing his trajectory may be inspiring a new model for chasing the dream, one that does not involve taking multiple gap years and agita for parents. The new model may emerge that you go to school, get your volume, fully exploit the domestic circuit and then, in skiing and in life, be ready to move on.

Both Lange and Knight acknowledge that managing college and elite skiing is not easy and may not work for everyone. Those willing to make the extraordinary commitment, however, should have the option. “There’s a time in your life, socially and intellectually, when you should go to college. Your mind is open and malleable,” says Knight, who is positive about what the UNI team has already accomplished in bridging what he calls the organization’s “massive cultural impediment from way back. Now our job is to try to make the programs continue to work,” he says. “It’s up to us to make its legacy successful.” Lange remains optimistic about the UNI team concept. “This program fits into U.S. culture,” he offers. “The other thing that I want dearly is to have every athlete leave the USST feeling valid. Few will make the top in the world, but they are amazingly good – just some are better than others.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article referred to a statistic in which development team athletes scored inside the top 30 but did not remain ranked in the top 30 for a full season. It has since been edited for clarification purposes.